Why Is the Family Considered the Most Important Agent of Socialization?

4.3 Agents of Socialization

Learning Objectives

- Identify five agents of socialization.

- Draw positive and negative aspects of the socialization these agents produce.

Several institutional and other sources of socialization exist and are called agents of socialization. The first of these, the family, is certainly the most important agent of socialization for infants and young children.

The Family unit

The family is perhaps the well-nigh important agent of socialization for children. Parents' values and behavior patterns profoundly influence those of their daughters and sons.

Randen Pederson – Family unit – CC Past 2.0.

Should parents become the credit when their children turn out to exist good kids and even keep to accomplish keen things in life? Should they get the blame if their children plough out to be bad? No parent deserves all the credit or blame for their children's successes and failures in life, but the evidence indicates that our parents exercise affect the states profoundly. In many ways, we even cease up resembling our parents in more than than just appearance.

Sociology Making a Deviation

Understanding Racial Socialization

In a social club that is withal racially prejudiced, African American parents continue to find it necessary to teach their children about African American civilization and to prepare them for the bias and bigotry they can await to come across. Scholars in folklore and other disciplines have studied this process of racial socialization. 1 of their most interesting findings is that African American parents differ in the caste of racial socialization they practice: some parents emphasize African American identity and racial prejudice to a considerable degree, while other parents mention these topics to their children only minimally. The reasons for these differences have remained unclear.

Sociologist Jason East. Shelton (2008) analyzed information from a national random sample of African Americans to determine these reasons, in what he called "one of the most comprehensive analyses to date of racial socialization strategies amongst African Americans" (p. 237). Amidst other questions, respondents were asked whether "in raising your children, have you done or told them things to help them know what it means to exist Black." They were as well asked whether "there are any other things you've washed or told your children to assistance them know how to get along with White people."

In his major results, Shelton found that respondents were more than probable to practice racial socialization if they were older, female, and living exterior the Southward; if they perceived that racial bigotry was a growing trouble and were members of ceremonious rights or other system aimed at helping African Americans; and if they had higher incomes.

These results led Shelton to conclude that "African Americans are non a culturally monolithic group," as they differ in "the parental lessons they impart to their children about race relations" (2008, p. 253). Farther, the parents who do practice racial socialization "practice so in order to demystify and empower their offspring to seize opportunities in the larger society" (p. 253).

Shelton'due south written report helps u.s.a. to understand the factors bookkeeping for differences in racial socialization past African American parents, and it also helps united states of america understand that the parents who do attempt to make their children enlightened of U.S. race relations are only trying, every bit most parents do, to help their children get ahead in life. By increasing our understanding of these matters, Shelton'southward enquiry has helped make a difference.

The reason we turn out much like our parents, for better or worse, is that our families are such an important part of our socialization procedure. When we are born, our primary caregivers are well-nigh always one or both of our parents. For several years we have more contact with them than with whatsoever other adults. Considering this contact occurs in our most formative years, our parents' interaction with united states of america and the messages they teach us tin can have a profound touch throughout our lives, every bit indicated by the stories of Sarah Patton Boyle and Lillian Smith presented before.

The ways in which our parents socialize usa depend on many factors, two of the near important of which are our parents' social class and our own biological sexual practice. Melvin Kohn (1965, 1977) establish that working-grade and middle-course parents tend to socialize their children very differently. Kohn reasoned that working-course parents tend to hold mill and other jobs in which they have petty autonomy and instead are told what to do and how to exercise it. In such jobs, obedience is an important value, lest the workers be punished for non doing their jobs correctly. Working-class parents, Kohn idea, should thus emphasize obedience and respect for authority equally they raise their children, and they should favor spanking as a primary manner of disciplining their kids when they disobey. In contrast, eye-class parents tend to hold white-neckband jobs where autonomy and contained judgment are valued and workers get ahead by being creative. These parents should emphasize independence equally they raise their children and should be less likely than working-class parents to spank their kids when they disobey.

If parents' social class influences how they raise their children, it is also true that the sex of their children affects how they are socialized by their parents. Many studies find that parents raise their daughters and sons quite differently as they collaborate with them from nativity. We will explore this further in Chapter 11 "Gender and Gender Inequality", but suffice it to say here that parents help their girls learn how to act and think "like girls," and they help their boys learn how to deed and think "similar boys." That is, they help their daughters and sons acquire their gender (Woods, 2009). For example, they are gentler with their daughters and rougher with their sons. They give their girls dolls to play with, and their boys guns. Girls may be made of "saccharide and spice and everything overnice" and boys something quite different, but their parents help them greatly, for better or worse, turn out that manner. To the extent this is true, our gender stems much more from socialization than from biological differences between the sexes, or then most sociologists probably assume. To return to a question posed earlier, if Gilligan is right that boys and girls reach moral judgments differently, socialization matters more than biological science for how they achieve these judgments.

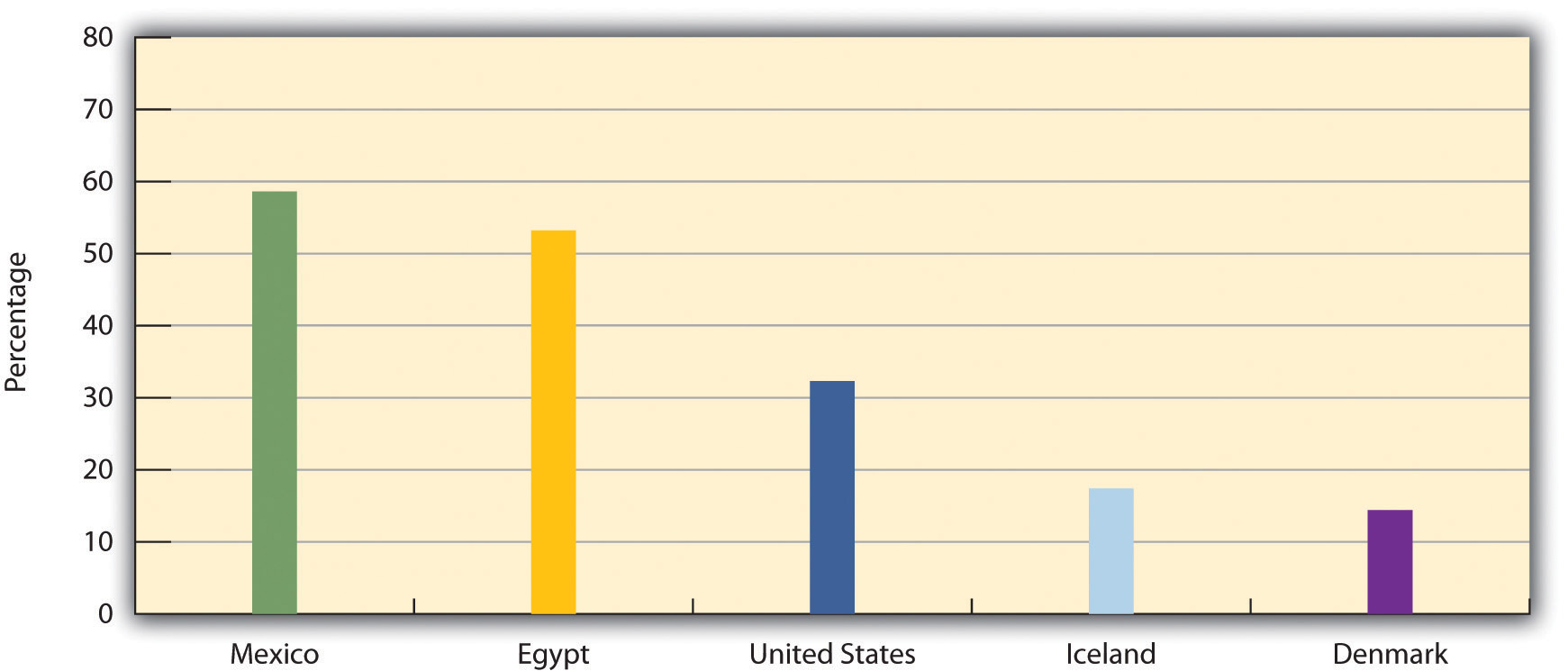

As the "Learning From Other Societies" box illustrates, various cultures socialize their children differently. Nosotros can also examine cross-cultural variation in socialization with data from the World Values Survey, which was administered to almost six dozen nations. Figure 4.1 "Percent Assertive That Obedience Is Especially Of import for a Child to Learn" shows the percent of people in several countries who think it is "especially important for children to learn obedience at home." Here we see some striking differences in the value placed on obedience, with the United States falling somewhat in between the nations in the effigy.

Learning From Other Societies

Children and Socialization in Japan

This affiliate ends with the observation that American children need to exist socialized with certain values in social club for our social club to be able to accost many of the social issues, including hate crimes and violence against women, facing it. As nosotros consider the socialization of American children, the experience of Nihon offers a valuable lesson.

Recall from Chapter 2 "Middle on Social club: Doing Sociological Research" that Japan'southward civilisation emphasizes harmony, cooperation, and respect for authorization. Socialization in Nippon is highly oriented toward the didactics of the values only listed, with much of it stressing the importance of belonging to a grouping and dependence, instead of individual autonomy and independence. This is specially truthful in Japanese schools, which, every bit ii sociologists write, "stress the similarity of all children, and the importance of the group" (Schneider & Silverman, 2010, p. 24). Allow'southward run into how this happens (Hendry, 1987; Schwalb & Schwalb, 1996).

From the fourth dimension they brainstorm schoolhouse, Japanese children learn to value their membership in their homeroom, or kumi, and they spend several years in the same kumi. Each kumi treats its classroom as a "home away from habitation," equally the children arrange the classroom furniture, bring in plants and other things from their own homes, and clean the classroom every day. At recess one kumi will play confronting another. In an interesting difference from standard exercise in the United States, a kumi in junior loftier schoolhouse will stay in its classroom while the teachers for, say, math and social science move from one classroom to another. In the The states, of course, the opposite is true: teachers stay in their classrooms, and students motion from one room to some other.

Other practices in Japanese schools further the learning of Japanese values. Young schoolchildren wear the same uniforms. Japanese teachers use abiding drills to teach them how to bow, and they have the children repeatedly stand and sit down every bit a grouping. These practices aid students larn respect for authorization and help enhance the sense of group belonging that the kumi represents. Whereas teachers in the Usa routinely telephone call on individual students to answer a question, Japanese teachers rarely do this. Rather than competing with each other for a good grade, Japanese schoolchildren are evaluated co-ordinate to the performance of the kumi as a whole. Because decision making within the kumi is washed by consensus, the children learn the demand to compromise and to respect each other'southward feelings.

Considering the members of a kumi spend so much fourth dimension together for so many years, they develop extremely close friendships and think of themselves more than equally members of the kumi than as individuals. They become very loyal to the kumi and put its interests higher up their ain private interests. In these and other ways, socialization in Japanese schools helps the children and adolescents at that place learn the Japanese values of harmony, group loyalty, and respect for potency. If American children learned these values to a greater degree, it would exist easier to address violence and other issues facing the United States.

Figure iv.1 Per centum Believing That Obedience Is Especially Important for a Child to Learn

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 2002.

Schools

Schools socialize children past teaching them their formal curricula only too a subconscious curriculum that imparts the cultural values of the social club in which the schools are institute. One of these values is the need to respect potency, equally evidenced by these children standing in line.

Schools socialize children in several means. First, students learn a formal curriculum, informally called the "three Rs": reading, writing, and arithmetic. This phase of their socialization is necessary for them to become productive members of their society. 2d, considering students interact every day at school with their peers, they ideally strengthen their social interaction skills. Third, they interact with authorization figures, their teachers, who are not their parents. For children who have not had any preschooling, their teachers are frequently the start authority figures they have had other than their parents. The learning they gain in relating to these authority figures is however some other important component of their socialization.

Functional theorists cite all these aspects of school socialization, but conflict theorists instead emphasize that schools in the United States also impart a hidden curriculum by socializing children to accept the cultural values of the society in which the schools are found. To be more than specific, children larn primarily positive things well-nigh the state's by and nowadays; they learn the importance of being slap-up, patient, and obedient; and they learn to compete for good grades and other rewards. In this fashion, they learn to love America and non to recognize its faults, and they learn traits that prepare them for jobs and careers that will bolster the backer economy. Children are too socialized to believe that failure, such as earning poor grades, stems from not studying hard enough and, more than generally, from non trying hard enough (Booher-Jennings, 2008; Bowles & Gintis, 1976). This process reinforces the blaming-the-victim ideology discussed in Chapter 1 "Sociology and the Sociological Perspective". Schools are also a significant source of gender socialization, equally fifty-fifty in this modern twenty-four hour period, teachers and curricula send out various messages that reinforce the qualities traditionally ascribed to females and males, and students appoint in recess and other extracurricular activities that do the same thing (Booher-Jennings, 2008; Thorne, 1993).

Peers

When you were a 16-yr-old, how many times did you lot complain to your parent(s), "All of my friends are [doing and so and so]. Why can't I? It isn't fair!" Every bit this all-too-mutual example indicates, our friends play a very important role in our lives. This is especially true during adolescence, when peers influence our tastes in music, wearing apparel, and then many other aspects of our lives, equally the now-common image of the teenager e'er on a cell phone reminds us. But friends are important during other parts of the life course too. We rely on them for fun, for emotional comfort and support, and for companionship. That is the upside of friendships.

Our peers also assist socialize us and may even induce us to violate social norms.

The downside of friendships is called peer force per unit area, with which yous are undoubtedly familiar. Suppose it is Fri night, and yous are studying for a big exam on Monday. Your friends come by and ask you to go with them to get a pizza and a drink. You would probably hold to go with them, partly because you really dislike studying on a Friday night, simply also because in that location is at least some subtle pressure on yous to do then. As this example indicates, our friends tin influence us in many ways. During boyhood, their interests can impact our own interests in movie, music, and other aspects of popular civilisation. More ominously, adolescent peer influences have been implicated in underage drinking, drug utilise, delinquency, and hate crimes, such every bit the killing of Charlie Howard, recounted at the beginning of this chapter (Agnew, 2007) (run into Chapter 5 "Social Structure and Social Interaction").

After we accomplish our 20s and 30s, our peers get less of import in our lives, particularly if we get married. Nonetheless even and so our peers practice not lose all their importance, as married couples with young children still manage to get out with friends now and and then. Scholars have also begun to emphasize the importance of friendships with coworkers for emotional and practical support and for our continuing socialization (Elsesser & Peplau, 2006; Marks, 1994).

The Mass Media

The mass media are another amanuensis of socialization. Television shows, movies, popular music, magazines, Web sites, and other aspects of the mass media influence our political views; our tastes in popular culture; our views of women, people of color, and gays; and many other beliefs and practices.

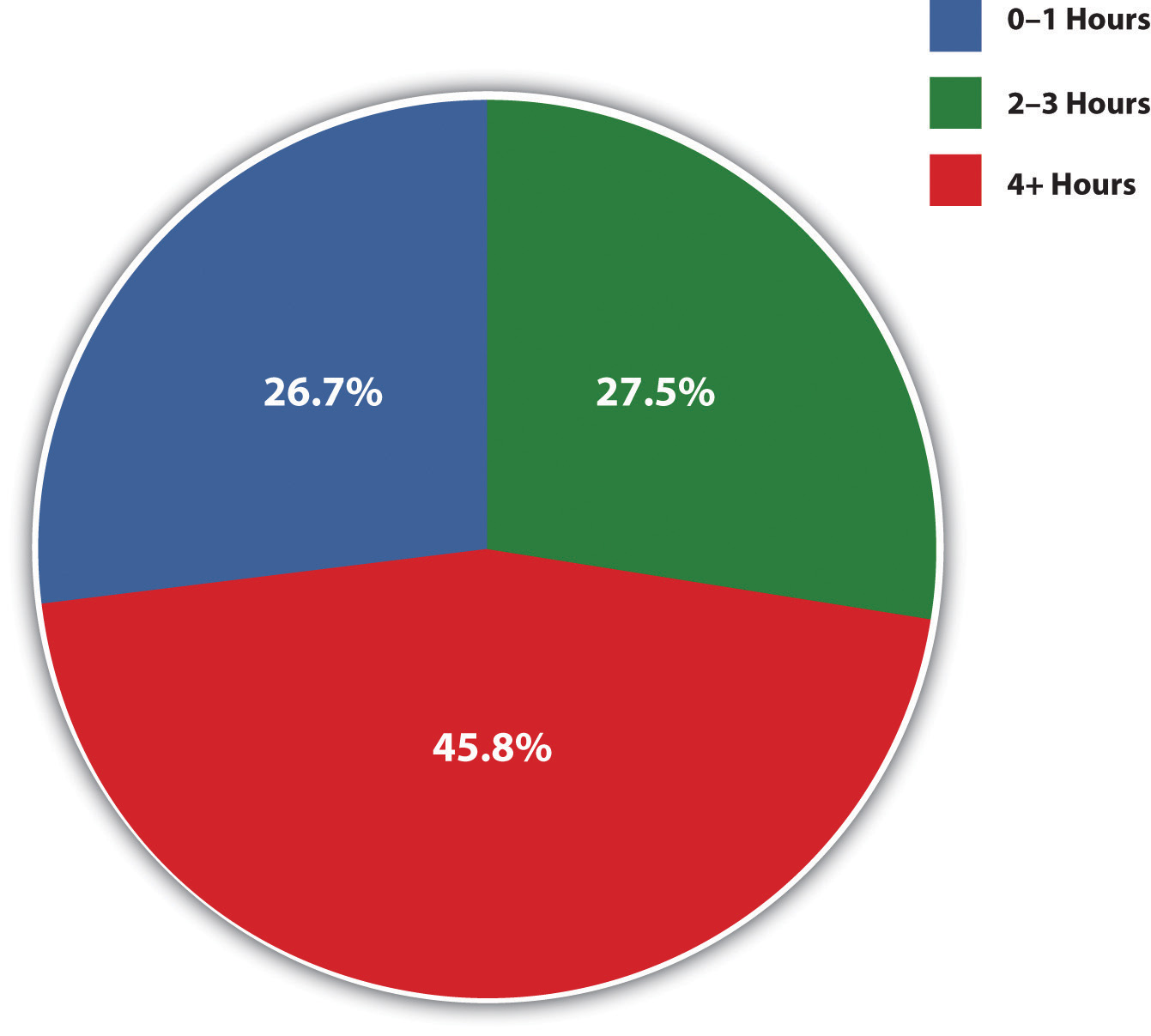

In an ongoing controversy, the mass media are often blamed for youth violence and many other of our society'due south ills. The boilerplate child sees thousands of acts of violence on television and in the movies before reaching young adulthood. Rap lyrics oftentimes seemingly extol very ugly violence, including violence against women. Commercials can greatly influence our choice of soda, shoes, and countless other products. The mass media as well reinforce racial and gender stereotypes, including the belief that women are sexual practice objects and suitable targets of male violence. In the General Social Survey (GSS), nigh 28% of respondents said that they watch four or more hours of television every day, while another 46% sentry two to iii hours daily (encounter Figure 4.two "Average Number of Hours of Telly Watched Daily"). The mass media certainly are an important source of socialization unimaginable a half-century ago.

Figure four.2 Boilerplate Number of Hours of Television Watched Daily

Source: Information from Full general Social Survey, 2008.

Every bit the mass media socialize children, adolescents, and fifty-fifty adults, a key question is the extent to which media violence causes violence in our society (Surette, 2011). Studies consistently uncover a stiff correlation between watching violent goggle box shows and movies and committing violence. However, this does not necessarily mean that watching the violence actually causes violent behavior: perchance people sentry violence because they are already interested in it and perhaps even committing it. Scholars continue to debate the effect of media violence on youth violence. In a free society, this question is specially of import, every bit the belief in this result has prompted calls for monitoring the media and the banning of certain acts of violence. Ceremonious libertarians argue that such calls smack of censorship that violates the First Amendment to the Constitution, whole others argue that they fall within the Outset Amendment and would make for a safer guild. Certainly the concern and debate over mass media violence will continue for years to come.

Religion

1 final agent of socialization is religion, discussed farther in Chapter 12 "Aging and the Elderly". Although religion is arguably less important in people's lives now than it was a few generations ago, it withal continues to exert considerable influence on our behavior, values, and behaviors.

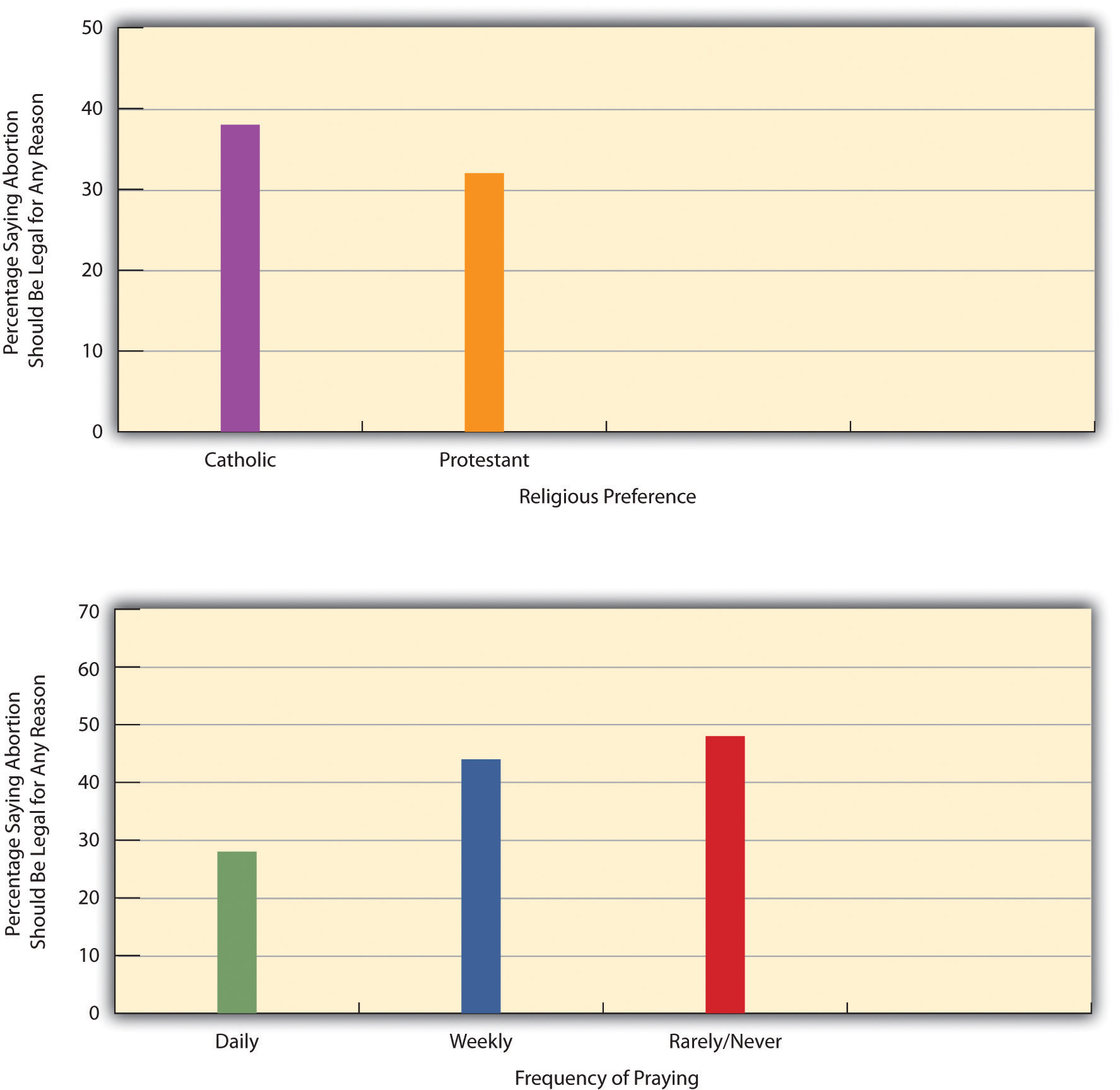

Hither we should distinguish betwixt religious preference (e.yard., Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish) and religiosity (e.chiliad., how often people pray or attend religious services). Both these aspects of organized religion can impact your values and beliefs on religious and nonreligious issues alike, but their particular furnishings vary from effect to effect. To illustrate this, consider the emotionally charged issue of abortion. People concur very strong views on abortion, and many of their views stem from their religious beliefs. Yet which aspect of religion matters the well-nigh, religious preference or religiosity? General Social Survey data help u.s. reply this question (Figure 4.three "Religious Preference, Religiosity, and Belief That Abortion Should Exist Legal for Any Reason"). It turns out that religious preference, if we limit it for the sake of this discussion to Catholics versus Protestants, does not matter at all: Catholics and Protestants in the GSS showroom roughly equal beliefs on the abortion issue, as most one-third of each group thinks abortion should exist allowed for any reason. (The slight difference shown in the table is not statistically significant.) However, religiosity matters a lot: GSS respondents who pray daily are only about one-half as probable equally those who rarely or never pray to think ballgame should be immune.

Figure 4.iii Religious Preference, Religiosity, and Belief That Abortion Should Exist Legal for Any Reason

Source: Information from General Social Survey, 2008.

Key Takeaways

- The ways in which parents socialize children depend in role on the parents' social class and on their kid's biological sex.

- Schools socialize children by teaching them both the formal curriculum and a hidden curriculum.

- Peers are an important source of emotional support and companionship, but peer pressure tin can induce individuals to behave in means they might ordinarily regard every bit wrong.

- The mass media are some other of import amanuensis of socialization, and scholars debate the effect the media have on violence in society.

- In considering the furnishings of faith on socialization, nosotros need to distinguish between religious preference and religiosity.

For Your Review

- Describe 1 of import value or mental attitude you accept that is the result of socialization by your parent(s).

- Do you agree that there is a hidden curriculum in secondary schools? Explicate your answer.

- Briefly describe 1 case of how peers influenced you or someone you know in a way that you now regard equally negative.

References

Agnew, R. (2007). Pressured into law-breaking: An overview of full general strain theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Printing.

Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Pedagogy, 29, 149–160.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reforms and the contradictions of economic life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Elsesser, K., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). The glass division: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Homo Relations, 59, 1077–1100.

Hendry, J. (1987). Understanding Japanese society. London, England: Croom Helm.

Kohn, M. (1977). Class and conformity. Homewood, IL: Dorsey.

Kohn, M. (1965). Social form and parent-child relationships: An interpretation. American Journal of Folklore, 68, 471–480.

Marks, Southward. R. (1994). Intimacy in the public realm: The case of co-workers. Social Forces, 72, 843–858.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global folklore: Introducing five contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Schwalb, D. Due west., & Schwalb, B. J. (Eds.). (1996). Japanese childrearing: 2 generations of scholarship. New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Shelton, J. E. (2008). The investment in blackness hypothesis: Toward greater understanding of who teaches what during racial socialization. Du Bois Review: Social Science Inquiry on Race, v(2), 235–257.

Surette, R. (2011). Media, crime, and criminal justice: Images, realities, and policies (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in schoolhouse. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Wood, J. T. (2009). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and civilization. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/sociology/chapter/4-3-agents-of-socialization/

0 Response to "Why Is the Family Considered the Most Important Agent of Socialization?"

Post a Comment